BIBLIOGRAPHY

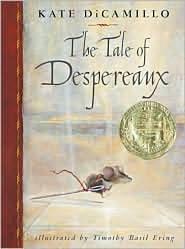

BIBLIOGRAPHYDiCamillo, Kate. 2003. THE TALE OF DESPEREAUX: BEING THE STORY OF A MOUSE, A PRINCESS, SOME SOUP, AND A SPOOL OF THREAD. Ill. by Timothy Basil Ering. Cambridge, Mass: Candlewick Press. ISBN: 0763617229.

*Winner of 2004 Newbery Medal*

PLOT SUMMARY

Once escaping the dungeon and his death sentence, Despereaux, a tiny yet big-eared mouse, becomes the unlikely hero when he saves his human love, Princess Pea, from the devious plans of Roscuro the vengeful and misunderstood rat and Miggery Sow, a slow-witted yet wishful castle servant.

CRITICAL ANALYSIS

The plot of The Tale of Despereaux: Being a Story of a Mouse, a Princess, Some Soup, and a Spool of Thread (or The Tale of Despereaux for short) is exciting and contains classic fairy tale elements. In this original take on a traditional tale of knights, fair maidens, and villains, DiCamillo has created a story of three main characters, Despereaux, Roscuro, and Miggory Sow, and how their lives are connected to and revolve around Princess Pea. The story moves at a wonderful pace as it tells the story of Despereaux innocently living against the mouse norms, of Roscuro who to would live not the darkness with the other rats but in the light, of Miggory Sow who dreams of becoming a princess but receiving laughs and “clouts” to her ears instead, and finally Princess Pea who a kind girl but is sadden by the lose of her mother. There are wonderful moments of humor and empathy for the characters during various parts of their story. A great element to the story is the fact that the mice and rats cannot only talk to each other, but they can also talk to humans. The plot truly grabs the reader into the story.

The part of the plot is its great presence of cause and effect. For nearly every act that is made there is an effect. It because one small action that a series of events take place. For example, it is because Roscuro went into the light, hung from a chandelier I the banquet hall then fell into the soup bowl of the queen, who died from the fright, that King Phillip outlawed soup, spoons and bowls, and rats. Another perfect example is at the climax of the story: because Despereaux had told a story to the jailer Gregory he was able to escape the dungeon under the napkin in Miggory Sow’s tray and learned of the devious plot that Roscuro was employing to the servant girl. If Despereaux had not read the book from the library he would not have known of the plot against his love.

The story is set in the Kingdom of Dor and in many areas of the king’s castle. The reader is taken from the little homes of the mice and their ventures into the castle rooms to eat like the library, Princess Pea’s room, to the dark dungeon (also called the deep downs), the banquet hall, the home of Miggory Sow’s uncle, and finally the kitchen. The book begins with the Despereaux’s birth during the month of April, and the plot continues in a forward fashion, however, there are moments when it will go back in time to begin or continue the sequences of events of another character. This classic setting allows DiCamillo to truly make the story of full of mice, rats, servants, a princess, a king, and banquets believable. However, this could also be taken out of the fairy tale setting and placed in a more contemporary setting. For example, this could be set in any large city. Princess Pea could become a well-to-do daughter of a successful businessman, Despereaux could be a mouse that is living in the house, Roscuro could be a rat that is living in the sewer next to the house, and Miggory Sow could be a girl from a underprivileged family that could be employed as the house cleaners. This story could also take on a western theme as well.

It is the characters that truly make The Tale of Despereaux a wonderful and exciting book. They are wonderfully bold and colorful. The reader is able to see the thoughts, feelings, and physical details of each character through not only the story’s narration but also through the dialog of secondary characters, Despereaux’s sister Merlot stating that his ears are abnormally big and his brother Furlough saying that he was born with his eyes open (DiCamillo, p. 13). The third way that the DiCamillo reveals the characters is through how the they react to certain events and other character actions, for example, the reader is able to see how Roscuro’s heart is like especially after it is broken by Princess Pea at the banquet and how it mended “crooked and lopsided” (p. 116).

To heighten their overall appearance and overall “real” and multi-dimensional, DiCamillo also provides the readers with insight into each character’s emotional strengths and weaknesses. Despereaux is a mouse with a large heart despite abnormal body and ear size, and because of his devoted love to Princess Pea overcomes even his self-doubt at times to become a hero. He is strong in convictions and will not succumb to the pressures and opinions that are set by his fellow mice. During sentencing with the Mouse Council, he refused to renounce his actions.

Roscuro is more complicated than other characters. His feelings change three times during the entire story. First he was rat wanting to live in the castle’s upstairs light and leave the dark dungeon. However, the first chance he got during the banquet he comes to the realization that he is a rat when Princess Pea calls him so and orders him back to the dungeon, which broke his heart that soon mended to “crooked and lopsided” (DiCamillo, p. 116) and he began his plan for revenge. The final change of Roscuro happens when his love for the light and for soup, which he had surpassed since the banquet, where stirred up when his revenge was foiled with Despereaux’s rescue of the princess.

Princess Pea also has multiple layers to her emotions and personality. Much like Despereaux, she too has a big heart. She is kind and “empathizes,” especially with Miggory Sow; however, she also has a twinge of hatred for Roscuro who is responsible for her mother’s death, and she also has sorrow for the lose of her mother. Miggory Sow may be considered the simplest of all of the characters. However, like her counterparts, she had experiences that shaped who she is. Despite her near deafness and her slow wit, which causes her trouble and is what Roscuro took advantage of, she is simply a good-hearted twelve-year-old girl who dreams of becoming a princess and who misses her deceased mother and missing father.

The greatest aspect of DiCamillo’s characters is that they do fall into the stereotypical molds that one would usually find in similar stories. Despite the initial preconceptions that are made my King Phillip and Princess Pea, Despereaux and Roscuro are the two major characters who do not follow the traditional ways of their kind. Despereaux is not like other mice. Instead of feeding on their pages, he reads books. He loves the sound of music and the human Princess Pea. He even talks to the humans. Roscuro, ultimately, goes against the norms of the other rats by loving the light. Princess Pea may be considered perfect, but she also holds that tiny bit of hatred for Roscuro, which does change to empathy at very end of the story. Though she may depict the typical servant girl who was a subject of miserable treatment, Miggory Sow is the not a servant girl that one would find working in castle. Because of her unique qualities she is practically unable to perform any services in the castle other than serving the jailer his tray of food.

Because of their uniqueness, the characters are also relatable to young readers. Readers can connect with Despereaux because not everyone is born physically perfect yet they are capable of doing impossible, which is much like the mouse’s growth from a sickly mouse to a hero because of his devotion to the princess. Also, like Despereaux children yearn for love and acceptance from family or from people he live with. Roscuro is the character that represents someone who wants something, such as living in the light, but was afraid of the consequences. Readers who have lost a loved one can relate to Princess Pea losing her mother. Finally, like Despereaux, young people can relate to Miggory Sow because not everyone lives with their parents, or live in a perfect household, or who are hard of hearing.

There are several themes within The Tale of Despereaux. The most predominate ones are good and evil and love. The conflict between the hero and the villains is the most classic theme in literature, especially fairy tales. The struggle between Despereaux and Roscuro follows this excitingly; however, instead totally vanquishing evil, the princess stops the mouse from killing Roscuro who in the end lives in between the light and dark. The second predominate is love. Love is the reason for many of the events that unfolded in the story. Despereaux loved music and the princess that sent him to the dungeon and to save the princess from dungeon. It is love that made Roscuro venture upstairs to the light but only to return with an ill-mended heart. Finally, it is because of the love of her mother that Princess Pea bravely followed her captors to the dungeon. Other underlining themes are bravery, forgiveness, empathy, and acceptance. All of these themes are all good aspects for young readers to read, and The Tale of Despereaux is a good example of presenting them in a non-moralizing manner.

The book is divided into four parts called books. The first three tell the story of Despereaux, Roscuro, and Miggory Sow. The final book relays to the readers what happens when all four characters come together and end the tale. DiCamillo’s writing is wonderful detailed and exciting. Through third-person omni-present narration, DiCamillo wrote The Tale of Despereaux much in the way that a child would imagine a fairy tale with a narrator who speaks directly to the reader. By speaking directly the reader, such as asking “do you know what ‘perfidy’ means?” then provides the meaning (DiCamillo, p. 44). This is a personal way for the author to connect to the reader and assist them in learning new words that are used in the story; however, older readers may find this as the author talking down to them. The overall presence of the narrator fits into the theme of a fairy tale because it very reminiscent a traditional chope orally telling the story to the reader.

There is a well balanced of narration and dialog use in the book. As discussed above, the two of them play an important role in providing the readers with descriptive information. They are also an extension of the character’s personality. Despereaux uses words that he had learned from reading the book in the library. Roscuro speech changes from a well-spoken rat to a smooth, sophisticated villain, then back to how he was at the beginning. Princess Pea speaks perfectly like a princess, and Miggory Sow shouts most of the time because of her hearing and uses the expression “Gor” quite often.

To explain and enrich the theme of good and evil, DiCamillo includes the metaphorical differences of light and dark. Light represents the goodness in the characters and darkness is evil. Even the wonderful illustrations by Timothy Basil Ering, depicts Despereaux in a halo of light and Roscuro, especially during his moments of villainy, in the shadows.

In the end DiCamillo’s The Tale of Despereaux is a fantastically unique story with strong characters with the wonderful essence of a fairy tale.

BOOK REVIEWS

HORN BOOK MAGAZINE

(Intermediate) Despereaux Tilling is not like the other mice in the castle. He's smaller than average, with larger than average ears. He'd rather read books than eat them. And he's in love with a human being--Princess Pea. Because he dares to consort with humans, the Mouse Council votes to send him to the dungeon. Book the First ends with Despereaux befriending a jailer who resides there. Books two and three introduce Roscuro, a rat with a vendetta against Princess Pea, and Miggery Sow, a young castle servant who longs to become a princess. Despereaux disappears from the story for too long during this lengthy middle section, but all the characters unite in the final book when Roscuro and Miggery kidnap Princess Pea at knifepoint and Despereaux, armed with a needle and a spool of thread, makes a daring rescue. Framing the book with the conventions of a Victorian novel ("Reader, do you believe that there is such a thing as happily ever after?"), DiCamillo tells an engaging tale. The novel also makes good use of metaphor, with the major characters evoked in images of light and illumination; Ering's black-and-white illustrations also emphasize the interplay of light and shadow. The metaphor becomes heavy-handed only in the author's brief, self-serving coda. Many readers will be enchanted by this story of mice and princesses, brave deeds, hearts "shaded with dark and dappled with light," and forgiveness. Copyright 2003 of The Horn Book, Inc. (September 1, 2003)

SCHOOL LIBRARY JOURNAL

Gr 3 Up-A charming story of unlikely heroes whose destinies entwine to bring about a joyful resolution. Foremost is Despereaux, a diminutive mouse who, as depicted in Ering's pencil drawings, is one of the most endearing of his ilk ever to appear in children's books. His mother, who is French, declares him to be "such the disappointment" at his birth and the rest of his family seems to agree that he is very odd: his ears are too big and his eyes open far too soon and they all expect him to die quickly. Of course, he doesn't. Then there is the human Princess Pea, with whom Despereaux falls deeply (one might say desperately) in love. She appreciates him despite her father's prejudice against rodents. Next is Roscuro, a rat with an uncharacteristic love of light and soup. Both these predilections get him into trouble. And finally, there is Miggery Sow, a peasant girl so dim that she believes she can become a princess. With a masterful hand, DiCamillo weaves four story lines together in a witty, suspenseful narrative that begs to be read aloud. In her authorial asides, she hearkens back to literary traditions as old as those used by Henry Fielding. In her observations of the political machinations and follies of rodent and human societies, she reminds adult readers of George Orwell. But the unpredictable twists of plot, the fanciful characterizations, and the sweetness of tone are DiCamillo's own. This expanded fairy tale is entertaining, heartening, and, above all, great fun.-Miriam Lang Budin, Chappaqua Public Library, NY Copyright 2003 (August 1, 2003).

CONNECTIONS

*Discuss the fairy tale elements that are found in the book.

*Discuss any foreshadowing that was hinted in the story by secondary characters.

*Compare Despereaux to other protagonists from books like Wilbur in Charlotte’s Web by E. B. White. How are they alike?

*Discuss the light and dark element of the story. What can they represent?

*Read more books about mice and rats such as the Poppy series by Avi, Mrs. Frisby and the Rats of NIMH by Robert C. O'Brien, A Rat's Tale by Tor Seidler, and Tales at the Mousehole by Mary Stolz

*Read more of Kate DiCamillo’s fantasies like The Tiger Rising and The Miraculous Journey of Edward Tulane.

Hi! I know that you wrote this post last year, but I have question I thought you might be able to answer. Do you know what the word "Gor" means that Mig uses all the time? I can't find anything that explains that, so maybe everyone but me understands it, but I would really like to know! Thank you!

ReplyDeleteHi Cynthia!

ReplyDeleteThat is a really good question. I just got The Tale of Despereaux at the library to read it again in preparation for the movie that comes out today (Dec. 19th).

Though I may not be 100% accurate, but after reviewing pertinent chapters here is my speculations of what “Gor” means:

We first learn about Miggory Sow in Book the Third. She begins to say “Gor” after her mother has died and her father had traded her to a man who clouts her ears. I am figuring that because of her upbringing with this “Uncle,” and because of the clouts to her ears, Mig says “Gor” as a way of saying “gosh” and/or as an expression that provides the readers another way to see who she is: a girl who is almost deaf (p. 143) and who is a clumsy and forgetful servant that has dreams of being a princess (i.e. it could be a expression that just pops out without her thinking about it).

It would be interesting to find out why author Kate DiCamillo decided to use the word. If anyone is interested in taking the chance to ask Kate, they can ask in a letter to the author at:

((Author or Illustrator's Name))

c/o Candlewick Press

99 Dover Street

Somerville, MA 02144

Maybe we’ll get lucky and she’ll respond (if so please share!). Also, if anyone has any better explanations of what “Gor” means, please share your thoughts!

I hope that this helps, Cynthia! Thank you for asking!