BIBLIOGRAPHY

BIBLIOGRAPHYTingle, Tim. 2006. Crossing Bok Chitto: A Choctaw Tale of Friendship & Freedom. El Paso, TX: Cinco Puntos Press. ISBN 9780938317777.

*Winner of the 2008 American Indian Youth Literature Awards*

*2008-09 Texas Bluebonnet Award Book*

PLOT SUMMARY

Living on opposite sides of the river Bok Chitto, which serves as the boundary line between the land of slavery and the land of freedom during the days before the Civil War, a friendship is formed between Martha Tom, a Choctaw Indian, and Little Mo a plantation slave. When Little Mo's mother is sold to another slave owner his family decide to run for freedom and must cross the river's secret stone path at night with the help of the Choctaws.

CRITICAL ANALYSIS

Crossing Bok Chitto is a powerful story of the connection between the Native American and the African American culture. There is a connection made between the importance of religion, he forbidden slave church, and Choctaw traditions. Each of songs or chants. In particular, there is beautiful imagery used in describing the Choctaw's wedding ceremony and the dresses that the women wear:

"Their white cotton dresses skimmed the ground and their shiny black hair dell well below their waists. The women formed a line and began a stomp dance to the beat of the chanting, gliding to a clearing at the end of town.

"When they reached the clearing, they formed two circles, the women and the men, and the wedding ceremony began. The old men began to sing the old wedding song. It is still sung today in Mississippi and Oklahoma, just as they sang it then

'Way, hey, ya hey ya

You a hey you ay

A hey ya a hey ya

Way, hey ya hey ya

You a hey you ay

A hey ya a hey ya!'"(p. 18).

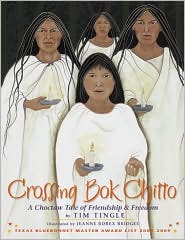

The illustrations are a combination of muted colors and flat yet beautifully bold realism. There is a strong emphasis on the facial features on of the the Choctaws and the African American slaves. In one instance when Martha Tom and Little Mo are standing side by side and their facial features are similar. The only difference is in the skin tones and hair, Lttle Mo is a rich dark brown with short tightly curled hair while Martha Tom his a rich light brown and has long black hair. Their eyes in particular are the same shape. This is seen through out the book and are used to to rely the emotions and expressions of the characters as well as the overall mood of the story. The clothing worn by the both the Choctaw and the African Americans are culturally accurate, especially in the case of the Native Americans. Martha Tom, her mother, and the men are seen wearing the non-stereotypical clothing and are befitting of the time that the story is set in. Readers will especially enjoy seeing the illustrations in which the slaves appear transparent as they are escaping the plantation and are invisible to the guards and their dogs. They will also love looking at the illustration at the end depicting the Choctaw women wearing their white cotton dresses at night and seeing them and the slaves walking the secret stone path in the Bok Chitto.

At the end of the story there is information on the Choctaws of modern times as well as "A Note on Choctaw Storytelling," in which Tingle discusses the power of storytelling. It does not, however, definitely say that the story of Martha Tom and Little Mo is true or simply a story that was created by combining numbers individual yet connected stories how the Native Americans helped slaves escape the south. This fact, however, does not take away from the overall story. Crossing Bok Chitto is a book that should be shared with readers of all ages and used in connection with other books and lessons on Native American and African American history.

BOOK REVIEWS

BOOKLIST

*Starred Review* Gr. 2-4. In a picture book that highlights rarely discussed intersections between Native Americans in the South and African Americans in bondage, a noted Choctaw storyteller and Cherokee artist join forces with stirring results. Set "in the days before the War Between the States, in the days before the Trail of Tears," and told in the lulling rhythms of oral history, the tale opens with a Mississippi Choctaw girl who strays across the Bok Chitto River into the world of Southern plantations, where she befriends a slave boy and his family. When trouble comes, the desperate runaways flee to freedom, helped by their own fierce desire (which renders them invisible to their pursuers) and by the Choctaws' secret route across the river. In her first paintings for a picture book, Bridges conveys the humanity and resilience of both peoples in forceful acrylics, frequently centering on dignified figures standing erect before moody landscapes. Sophisticated endnotes about Choctaw history and storytelling traditions don't clarify whether Tingle's tale is original or retold, but this oversight won't affect the story's powerful impact on young readers, especially when presented alongside existing slave-escape fantasies such as Virginia Hamiltons's The People Could Fly (2004) and Julius Lester's The Old African (2005). Jennifer Mattson Copyright © American Library Association.

SCHOOL LIBRARY JOURNAL

Grade 2-6–Dramatic, quiet, and warming, this is a story of friendship across cultures in 1800s Mississippi. While searching for blackberries, Martha Tom, a young Choctaw, breaks her village's rules against crossing the Bok Chitto. She meets and becomes friends with the slaves on the plantation on the other side of the river, and later helps a family escape across it to freedom when they hear that the mother is to be sold. Tingle is a performing storyteller, and his text has the rhythm and grace of that oral tradition. It will be easily and effectively read aloud. The paintings are dark and solemn, and the artist has done a wonderful job of depicting all of the characters as individuals, with many of them looking out of the page right at readers. The layout is well designed for groups as the images are large and easily seen from a distance. There is a note on modern Choctaw culture, and one on the development of this particular work. This is a lovely story, beautifully illustrated, though the ending requires a somewhat large leap of the imagination.–Cris Riedel, Ellis B. Hyde Elementary School, Dansville, NY

CONNECTIONS

*Read Tim Tingle's other picture book When Turtle Grew Feather: A Tale from the Choctaw Nation.